2009

8.9

There is really no need to introduce Pixar Animation Studios. No need to explain how, over the past 15 years, Pixar has released the most timeless and transcendental animated features since the golden age of Walt Disney. Furthermore, it is pointless to note that Pixar is a studio comprised of adults making sophisticated and thoughtful films, consistently marketed toward children, that obliterate age demographics. Instead let's focus on the micro evolution of Pixar's thematic content and vision. Toy Story was primarily a singular childhood fantasy which dealt with the less than instinctive practice of social acceptance. Finding Nemo used a dual narrative in order to find common ground between the desires of children and the protective qualities of overbearing parents. Ratatouille etched a beautiful portrait of the relationship between independence and interdependence in romance and society. WALL-E delivered a universal (and overtly political) message against ennui and the distractions of the digital age. With Up, Pixar's 10th feature, the studio has delivered its foremost adult film. With themes of aging, loyalty and the burden of memory, Up is Pixar's most finely cultivated and quietly introspective film yet.

Known more for humanizing marginalized animals and objects (fish, rats, toys, robots, etc.), Up is only Pixar's second film to exclusively follow human characters. Moving beyond the familial adventure of The Incredibles, Up is both familiar and unfamiliar to the studio's filmography. To begin, its principle character is a senior citizen. At first this choice may seem unorthodox but Pixar brings in familiar elements to marry the film with the rest of its canon. First, the tried and true “unlikely ensemble”: the old man (Carl), a pudgy and useless boyscout (Russell), a 13 foot tall exotic female bird named Kevin, and a “talking” dog called Dug. Second, the growth of the principle character who remains obstinately insular until an emotional breaking point whereupon he commits himself wholeheartedly to righteous morality and the happiness of his companions. Pixar's films could be considered structurally formulaic in this sense, but each navigates its scenario in a way that is so thrilling and highly involved that the complaint becomes virtually invalid.

In each of Pixar's films there is some sort of initial disturbance ranging from the innocuous arrival of a new toy to the capture of a fish's sole offspring. These are the moments, which are usually affixed with modest tension, which catapult the narrative into motion. Up doesn't necessarily break this pattern but the film does structurally postpones its ascent into linear narrative. Beginning with Carl's childhood and the meeting of his eventual wife Ellie, the film enters a harrowing and emotionally wrenching montage that encapsulates the passing of time and the strife of two lovers. It is unveiled that Carl and Ellie's dream is to travel to South America and discover the enchanted lands of Paradise Falls, which first captured their mutual imagination when they were children. However, as so often happens in the real world, events interject. As the montage progresses there is shot after shot of a glass coin jar, which contains their funds for the trip, smashed in order to recover from loss (injury, destruction, etc.). The montage is particularly moving in its dealing with two mature themes which are broached silently and sadly: an incapacity to have children (or perhaps, worse still, a miscarriage) and Ellie's death. Cinematically masterful this montage serves a very special function for the rest of the film: it injects meaning into personal objects causing them to later become representative of Carl's memory.

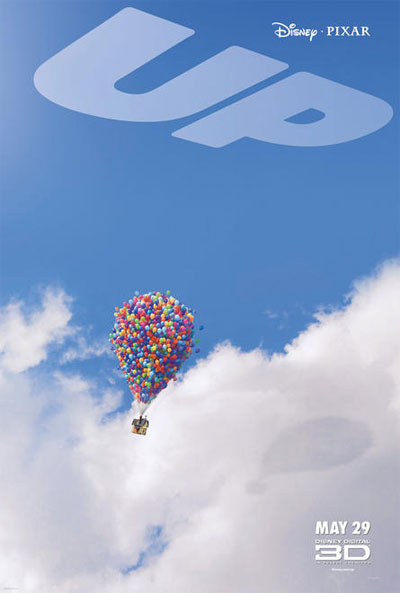

Carl, after battering a civil servant and being ordered to abandon the house he has lived in for most of his life, inflates thousands of balloons and soars into the sky toward South America. The rest of the story is an exercise in classic Pixar adventure, although at times the film works a little too hard to overcome its own sentimental inertia. Carl remains dedicated to the house which has become the embodiment of his dead wife. Even with the buoyancy of adventure (which the balloons represent) the house (Carl's memory) still remains a burden to him until circumstances arise that force him to choose between this precious relic of his past or a new life of meaning. Choosing the latter, there is a beautiful and iconic shot of the house, colored balloons still tethered to it, sinking away into the clouds: a weighty and powerful memory finally being released by its owner.

Back in 1995 I was seven years old and likely polishing off the last of the Walt Disney classics that I was raised on. That same year Pixar released its first feature and, in retrospect, its safe to say that a new epoch began. While Toy Story's animation was groundbreaking then (and still remains a milestone in digital animation) it is a “child's plaything” in comparison to Pixar's recent accomplishments. Known for their uncanny attention to detail, since the turn of the century the studio's animators have exploded into larger and larger digital environments. From countries to continents; the epic vastness of the ocean to the infinite reaches of the universe, Pixar has visually transported viewers to the very limits of imagination. Though it may seem a somber step back from WALL-E's intoxicating spectacle, Up moves viewers in a distinctly different way: emotionally. The subtlety and communicable depth of the film far exceeds anything yet achieved by Pixar. Though not without fault, Up is yet another massive achievement from a studio still reinventing itself and redefining popular cinema.

No comments:

Post a Comment