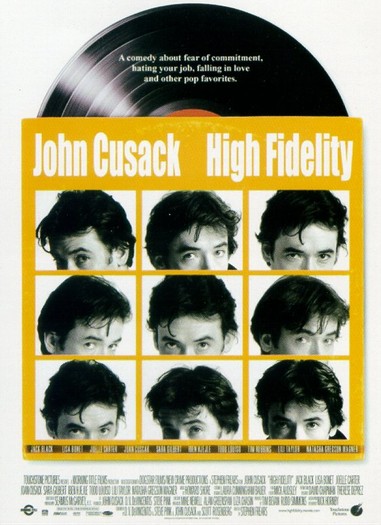

2000

8.5

Let's make things clear: if you don't enjoy High Fidelity you're an asshole. No offense. Now let's make another thing clear: I said “enjoy” not “like”. Like how you “enjoy” grilled cheese sandwiches but “like” filet mignon. High Fidelity is cinematic grilled cheese. It is simple, rarely overstated, warm and comforting; satisfying but not nutritional. It is something of a guilty pleasure. Around the turn of the century High Fidelity could be seen alongside David Fincher's Fight Club, the Coen Brothers' The Big Lebowski and Richard Kelly's Donnie Darko as popular, style driven cinema that contained a somewhat heavy handed, yet earnest subtext on the decay of contemporary American society. High Fidelity takes place in a more idiosyncratic universe than any of the aforementioned films and its subtext is the most precise. Where those films commented on the absurdity of the modern world from a pedestal of intellectualism High Fidelity bravely faces the reality of social deterioration and disconnection from reality. By doing so the film rejects the fatalistic myth of the inevitable end of culture those films seek to propagate.

Shifting gears slight I will now embark on a Top Five List of the things I did not “like” about High Fidelity:

1. The meta narrative. Best described by the author of the text to which the film owes essentially everything as a film in which “John Cusack reads [my] book.” A film of two hours that dizzyingly introduces the audience to every delirious detail that enters protagonist Rob Gordon's (Cusack) head, there is little credence given to the audience's ability to figure things out about Rob for themselves. More importantly, there is little reason, at least at first, for them to want to.

2. Exposition. As if it wasn't bad enough that Rob explains everything he's thinking, at least he takes on a flawed full development due to to his speaking and believing both lies and truth. Moving beyond character monolog, the film persists in explaining or summing up characters' traits and motivations in and through dialog. A record store crony rightly states what the audience figured out 30 minutes prior: the record store employees Rob, Dick (Todd Louiso) and Barry (Jack Black) are cultural snobs and musical elitists. A mutual friend of Rob and his now ex-girlfriend Laura (Iben Hjejle) quite deliberately asks Rob why he wants to be with Laura, well after the average audience member has asked themselves the same thing.

3. Pace. The whole story line of Rob's working though of his romantic hang-ups is indiscriminately rushed and then slowed. The film plays like Ferris Bueller's Day Off (protagonist displaying exaggerated self-awareness which is little more than egomaniacal self-image) meets Dickens' 'A Christmas Carol'. He submits himself to an uncomfortable journey through his past (nostalgic and overly romanticized), his present (a queer mix of apathy and resentment) and his future (optimistic via uncertainty). The audience is either rushing headlong through Rob's subjective monolog or hanging pitifully on single moments overburdened by an insinuated romantic longing that seems to exist only outside of the frame.

4. Genre. This is nit-picky but the film is billed as a romantic comedy although it tends toward being a dissection of Rob's psychology, piteously lauding over every contradiction. The romance between Rob and Laura is average if only slightly understated. Between Rob's delusional rants, his co-workers deplorably detached Top Fives, and smirk worthy scenes of name dropping, the majority of the love story ends up being little more than a few scenes of Laura passionately trying to explain what is obvious to everyone except Rob. In the film's final 20 minutes after a funeral and a long overdue apology, Rob and Laura sort of reconcile and Rob rejects the virtues of “the perfect stranger” in favor of the real Laura. This scene amounts to the film's only truly romantic moment.

5. Laura. Here I will voluntarily become the asshole: Iben Hjejle's acting is burdoned by her lack of fluency in English. Director Stephen Frears choice of casting in this case is a bit of head scratcher.

Having laboriously mapped out my problems with the film, I still stand by my introductory paragraph. In fact I will go as far to say that the entire review of this film is slightly superfluous. The real reason anyone should enjoy High Fidelity is because it is one of those truly rare films that knows exactly what it is. It does not have the pretense to be something it is not. Pointing out the flaws of the film is like pointing out how the male characters in the film detach themselves from reality through obsessive categorization, ego and superficial assumptions of superiority that amount to little more than a shield to protect themselves from the merciless tendencies of the real world. It's a slacker romance which tends to forgoe its romance for the sometimes interesting, sometimes obvious psychology of its protagonist. Its a music nerds dream film and also their worst nightmare. It deconstructs the myth of cool and delivers a well meaning eulogy for emotional relations.

Most importantly, this subtext of interaction over isolation has taken on greater meaning in the ten years since the film hit theaters, during which time popular digital realms have further separated people from each other and themselves. The quaintness of the 1990s (an anachronism already at the turn of the century) presents the perfect venue to put the digital vs. analog trial into a human perspective: the very analog process of working it through with yourself and others and the very digital process of hiding under whatever is available to hide under (ie. ego-centricity and emotional detachment). Though he could have not completely anticipated it at the time (2000 marked the zenith of Napster and the birth of the mp3 age) and there is a marked absence of any serious debate between digital and analog musical processes in the film, director Stephen Frears illustrates a complex web of modern relations using the late 90s as the final, picturesque days before the emotional apocalypse of the digital age.