2006

9.3

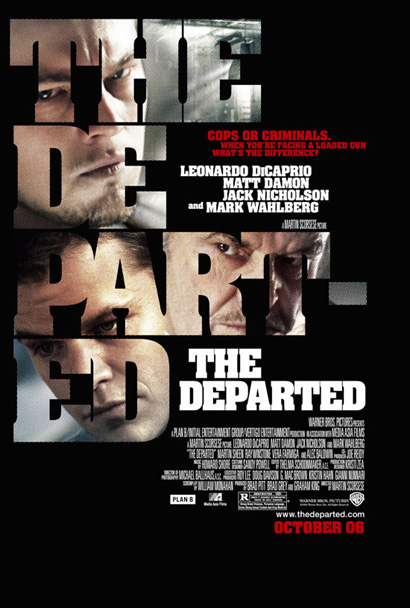

One could argue that The Departed pointed to an elevation in Scorsese's consideration of women. However, the recurring motifs of sons, impotence and sexlessness, which could potentially be used to support this point, do more to increase the insecurity and fallibility of the principle male characters than to heighten the stature of the film's neglected females. In fact the film's only principle female role functions more as a meeting point for the film's two deceivers, and her character is flat and remotely lifeless. However, this is the only flat and lifeless portion of the film. Trying to summarize the film's plot would indeed be an unfortunate decision at this junction. With The Departed Scorsese unleashes a hail of details in conjunction with violent sensory overload (the often discontinuous diegetic system alone is brilliantly disconcerting) that literally leaves the viewer stunned. This is perhaps Scorsese showing his own form of dominance over a genre that he helped define and keep alive since the 1970s.

Though Scorsese does not adhere to standard thriller film levels of suspense and detail, he roughly maintains their ratio. Not only are the levels of plot detail and visual excitement simply extraordinary, Scorsese imbues his film with his own polished psychology theories. There is, of course, the symbiotic relationship of law and crime which is explored in most every “crime” movie, but rarely to such a degree. The film's recurrent “what's the difference?” theme (facing a loaded weapon, cui bono?, could I do murder?) finds deep roots in the Neitzchaen principle of moral superiority or “beyond good and evil.” Direct references are made to Freud, however they are more for emphasize on the undercurrent of philosophy pounding in the blood of this film rather than for intellectual vanity. Scorsese takes his film is so many exciting directions at once that it's hard to recognize, even after several viewings, what is actually stimulating you. The Departed marks the difference between a film that is too complicated and poorly handled and one that the viewer gets more out of every time they watch it. It's a difference that's difficult to quantify but William Monohan's screenplay masterfully fills every crevice of curiosity and follows each loose end to its respective conclusion. You get done watching The Departed and you don't scratch your head and go “Huh?”. Instead, you feel like you need to go lie down or take a walk. You feel like you've just finished something seriously involving although you've only been sitting on your couch. In short, it's exactly how a movie should make you feel.

Despite all his achievements both in The Departed and its predecessors, Scorsese has still not managed to completely level with women. To illustrate, think of The Departed's final sequences as sex. The phallic-pistol erupting, which here would represent the male orgasm and directorial climax, causes the death of Costigan (which the viewer has unknowingly been anticipating) and the voyeuristic peak of the viewer's (representative of women) climax as well. This moment would have been the perfect cinematic rendering of mutual pleasure between director and viewer, had not two more murders taken place within seconds of that initial one and one more just before the final credit sequence roles. These sequential murders become symbolic of selfish pleasure (taken on by the director) for which we feel very little. They feel vaguely excessive and cheap: a means of ushering the film's finale which, while not rushed, doesn't feel entirely appropriate. Perhaps its our ingrained sense of American, bureaucratic law and order that informs our conviction that someone should have been arrested, although our most basic and instinctual sense of justice is satisfied with the final death. Nevertheless, Scorsese is surely putting the finishing touches on a grotesque portrait of primal urges. In doing so, however, he almost involuntarily associates himself with the engendered and dealt-with flaws of the characters he portrays so brutally. The act is corrupted and dangerously indulgent. It exercises the same system of desire etched out by the mob itself. For a film so sophisticated its conclusion feels unnervingly primitive. Perhaps it is best to conclude by saying that even a film as well thought out and executed as The Departed still cannot help but give insight into the mind of the man behind it.

No comments:

Post a Comment