1998

6.0

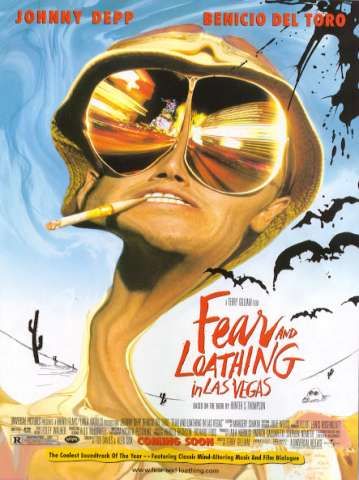

Several directors have attempted to adapt Hunter S. Thompson's magnum opus Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. It was hyperrealist Terry Gilliam who finally translated Thompson's intoxicating vision of a post-Love/Vietnam era America to the silver screen. It's not difficult to see the arresting appeal of Thompson's work especially to a visual filmmaker like Gilliam. Artistically the text falls far left of Norman Mailer and Tom Wolfe, opting for autobiographical involvement rather than journalistic detachment, but lands a little closer to center than William S. Burrough's seminal Naked Lunch, with its manic moods and recondite prose. Thompson's invented technique of Gonzo Journalism, utilized in this famed outing, fused the narrative elements of fiction with the cerebral objectivity of a reporter in the field, attempting to create a seamless, unconscious reporting; a sort of journalistic automatism. The start of the novel, the significant Dr. Johnson quote “He who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man,” identifies both the central theme of the text as well as Thompson's intent. By subjugating the superego to the primitive ferocity of the id, through whatever means or substances deemed necessary, Thompson planned to reach anti-enlightenment: a state of mental and physical suffering so savage and visceral that he might truly escape the burdens of mankind. Hunter S. Thompson called Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas a failed attempt at Gonzo journalism. Sadly, Terry Gilliam's version fails as well, offering nothing more than a boiled down “greatest hits” version of this dizzying psycho analysis of America and its system of values at the turn of an epoch.

Gilliam's film begins its transgressions immediately. Before introducing the aforementioned Dr. Johnson quote, Gilliam juxtaposes stock footage of Vietnam protests with an eerily sweet rendition of “Favorite Things”. Despite being unnervingly Lynchian, Gilliam changes gears instantly with Johnny Depp's introspective and unabashed voiceover monolog and those tone setting opening lines. Immediately the contradiction becomes clear. Thompson sought to expose himself to the very horror of the American Dream letting his poetic stream-of-consciousness transport the reader directly into the story. The novel reads like a post-modern Heart of Darkness set on the west coast of America during the early 1970s. Rather than deliberately satirize his subjects Thompson's sharp prose and witty insights were mere footnotes to the shameful story that was unfolding right before his eyes. Gilliam's method, on the other hand, is contrived due at least in part to his medium. Gilliam, an internationally celebrated visual auteur, is an entertainer whose awe-inspiring vision occasionally detracts from any socio-political message he intends to broadcast. Example: Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas attempts savage satire and ends up being 90 percent slapstick and Gilliam's hallucinatory vision of American dystopia. The film's opening montage may be the director wearing his soul and feelings naively out on his sleeve (or perhaps vainly trying to attract viewer sympathy through emotional coercion), but the greater embarrassment is how he immediately rescinds them, destroying any value they might have had to the audience who will no doubt begin to wonder just what motivated Gilliam to adapt such a novel in the first place.

There are, however, a couple of sincere moments of filmmaking which fit nicely into the film's narrative framework. The first is the most celebrated and oft-quoted section of the novel: the “wave” speech. Epic, universal and beautifully written, this passage is fitted with an appropriately understated scene of Thompson/Duke (Johnny Depp) staring thoughtfully out the window of his Las Vegas hotel. The second moment is longer and of greater impact. In a North Vegas diner Gilliam puts together the finest set piece of the film, wherein Dr. Gonzo (Benecio del Torro and his incredible beer gut) demonstrates the much down played dark side of the drug abuser while Duke sits watching with ambivalent detachment as the diner's waitress turns to stone at the sight of Gonzo's hunting knife. Perhaps most terrifying of all is the sobering realism of the scene. The viewer is desperately and emotionally drawn into what is otherwise a circus of vivid visual effects and simplified contemporary philosophy.

Despite its many faults including a shamefully pro-drug conclusion ( or pro-madness in respect to Gilliam's oeuvre), Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is not so much a singular misguided attempt at cultural critique but rather a sign of the times. It misses genius and controversy (the two statuses Gilliam professed to desiring most from the project) but alongside films like The Matrix and Fight Club emerged as a stylized signifier of a new decade of decadence and depravity in cinema. These films look incredible, come loaded with easily digestible subtext and end up offering an ambivalent moral open endedness. If there is no longer a voice like Thompson's in the literary world to put into apocalyptic and rapturous terms the very tangible horror of our time it is a small comfort having a filmmaker like Gilliam who can translate those same potent thoughts into moving pictures while other more uncompromising artists pick up the inspirational slack. Though it fails to be much more than an impotent screen adaptation of a visual, entertaining and culturally revealing novel, Gilliam's Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas succeeded in introducing the text to a new generation, resurrecting the timeless and restless message of Hunter S. Thompson.

No comments:

Post a Comment