2001

This review is dedicated to the dialectical frustration of the film it purports to critique...

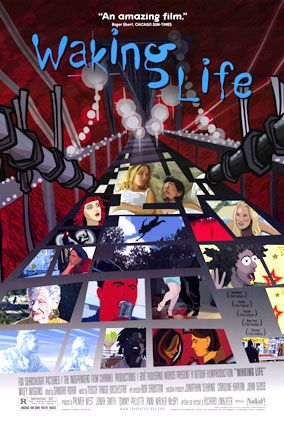

There is a fundamental contradiction latent in Richard Linklater's Waking Life. The film speaks at length about consciousness, mobility, living and being alive but in order to view the film we have to sit on our couch and experience the film passively; let the waves of progressive animation break over us; drown in its moody, philosophical diatribes; surrender to the stupefying experiences that is Waking Life. In utilizing this process I think Richard Linklater is trying to gesture toward film's existence in a “world of the dead”; a world of semantic visual language that, since its birth, has come under closer and closer constrictions until finally it arrives at its current state: modern cinema with all its limitations, both inherently in the medium (physical) and outside of it (financial), structurally built into the system by which all film comes to be and be seen. Of course the biggest contradiction of all is Linklater's voice in Waking Life. Is the film a serious testament to the myriad ways in which human beings find reason to live and connect with people? Or is it an ironic document, psycho analytically detached from its subject matter, about the hypocrisy of people preaching an active existence but who live in a constant state of ideas and dreams?

In honor of Linklater's subversion of narrative form I will self-destruct my own critical narrative. Here are two spoilers: 1) I hated this film. 2) The answer to the question above (and to all the questions posed throughout the film) is: there is no answer. In reference to the first spoiler I defend my tactless denunciation by suggesting that the conscientious film lover discovers a paradox in Waking Life. The viewer does not necessarily hate the film it is “bad”, in the critical and hyper objective sense, but rather because the film is actually not much of a film. It is a collective stream of consciousness that forms no parallels and obeys no laws. It adheres to no preconceived rules and thus ends up being some form of mutant neo-cinema. Yes, we view it projected on to screens or flashed onto our televisions like any other film, but Waking Life operates in complete opposition to the expectations of even the most well-viewed movie fan. The film transgress its initial self-awareness (a scene of studio musicians recording the film's eerie score) and enters a bizarre state of permeability between the viewer and the nominal protagonist.

The viewer is dragged into the film via fantasy POV shooting and is addressed directly by the film's hyper stylized characters (many of whom are rotoscoped versions of Linklater collaborators and friends). This faux-documentary style is all the while counterbalanced by the abstract narrative of our “protagonist” and his journey from unconscious observation to conditioned awareness. The viewer takes this journey in just the opposite direction, initially perturbed and offset by almost every aspect of Linklater's film and later completely entranced by it. The intensity of Linklater's audiovisual process, which some have suggested to be in sync with the film, while being hugely impressive is nonetheless completely distracting, disconnecting the viewer from the essasyistic network of ideas which Linklater has scrupously collected and loosely connected to one another. As the final credit sequence rolls the viewer has either completely rejected the film or accepted blindly its aura (and potential illusion) of knowledge, creativity and enlightenment.

To call this film difficult would be a dramatic understatement. In fact, it is nearly impossible. The film is conceived as a series of hallucinatory episodes, from the sublime to the intensely visceral, meant to mimic the dreamscape in which all the unconscious thought process an individual might have throughout their life is articulately stated by a number of talking heads. The films title and preeminent theme (if one may be so bold...) is that of the differences and similarities between the world of dreams and the “waking life” which is, of course, discussed at length, with Linklater tediously wandering from one semi-plausible explanation to the next. Perhaps the film's most inadvertently pleasing facet is how this “waking life” is referred to us by its opposite: the film. The film, which is a pure construct, drawing attention to its own construction through its dynamic animation and the absurdity of its non-linear structure, reminds us that outside of this film there is a whole life that we are meant to interact with. But therein lies the problem. Is this the climax of Linklater's eulogy on life or the punch-line to a nasty joke?

As formerly stated that troubling question remains unresolved. The obsessively nomadic structure means the viewer is never firmly rooted in one idea before he is lifted off to another one. Affective film making is scattered throughout, but the Waking Life is mostly an authoritarian and derisive approach to the communication of ideas. Where hints of the celestial may appear they are immediately stomped out by the coldness of the cerebral, punished for their attempts at transcendence. The film ends up being an elliptical meditation on life, death, dreams and how all three (apparently) relate to one another. It invites contemplation and active participation without ever leaving your living room. It is thus a contradictory statement, one that attempts to wield far too much control over its own contradiction, and as a result becomes the perfect example of art's uselessness. Utterly didactic and un-fulfilling, through Waking Life Richard Linklater has abandoned his duty as a filmmaker in order to tell (at length) instead of show, proclaiming all that is absorbing, arresting and illuminative in both fiction and non-fiction because it is communicated intrinsically rather than letting the film divulge its hidden self.

No comments:

Post a Comment