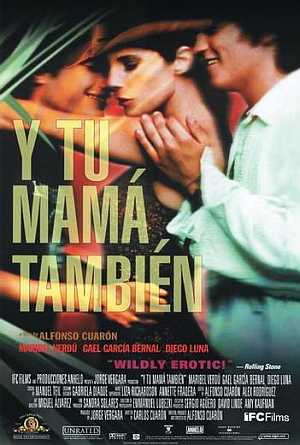

Dir. Alfonso Cuarón

2002

9.7

People tend to view their individual progressions through time geographically. Youth and adolescence is a slow climb toward a plateau which eventually becomes a slow or rapid descent into the valley that is our departure from the mortal world. I prefer to see life musically. The first two decades or so are a slow crescendo, a quick and lively section that ultimately reaches the point at which the music remains the same volume for a long period of time. Nevertheless, during this passage of uniform loudness there are plenty of unique moments that never fail to elicit some form of reaction. The phrases become more and more complex; there are key and tempo changes; notes are missed while others are just a few cents off. Sometimes there is the passion of vibrato and other times the staleness of pizzicato. And then, just like that, the music tapers off until the final, resounding chord is struck. It is this chord which ultimately defines the entire piece. If we choose to use this life as music metaphor than there are few contemporary pieces more violently dramatic and emotionally rich than Alfonso Cuarón's Y Tu Mamá También, an insurmountable work of genius film making that synthesizes the director's immediate sense of naturalism and his beyond-brilliant ability to capture symbolic details latent in everyday life.

The film's primary theory, the one that drives its inner and exterior conflict, is the notion that truth is partial. As primary characters, thoughtless teenagers and best friends, Julio (Gael García Bernal) and Tenoch (Diego Luna) explain to sexy, heartbroken Luisa (Maribel Verdú) that truth is cool but “unattainable.” The irony of course being that as 18 year olds living in Mexico City (set against the backdrop of the turn-of-the-century Mexican socio-political clash between the ruling bourgeois and mutinous proletariat) who spend most of their time partying and masturbating, Julio and Tenoch have a very limited concept of “the truth.” After meeting Luisa, the boys begin to plan a road trip that will result in the culmination of their desires: a satisfying (which to teenage boys is of course a very partial term) sexual experience with Luisa, which essentially represents their seamless transition into adulthood. What happens instead is the painful growth of their consciousness, their evacuation from their sheltered childhood, the ultimate demise of their friendship and their reaching the point at which the music of their respective lives will remain at the same volume. In other words: their true transition into adulthood.

This is the bare story. So much happens that it is difficult to contextualize the abundance of details that enrich the narrative, never mind analyze the film's sublime subtext of shrinking and burgeoning life experiences. The style of the film alone is a pamphlet on Expressionist modes of communicating in cinema. Emmanuel Lubezki, one of my favorite contemporary cinematographers, utilizes a spiritual, subjective third person view point. Spiritual, in the sense that the camera is not omnipresent but rather is subject to the limitations of our temporal universe. His camera wanders throughout the homes of Julio, Tenoch and Luisa, positions itself in the remaining passenger seat in Julio's car, and is limited by the physical restrictions of a regular person. This constraint actually becomes a means to an end. Lubezki uses it to produce creative, awe-inspiring and fluid shots, working the camera in harmony with his surroundings rather than forcing the opposite. Lubezki's cinematography exemplifies a whole new level of voyeurism that is emotionally subjective, allowing the viewer to be interpolated into the visceral experience of the film.

And still the film barrels on toward its psychological train wreck of a climax. While on the road Luisa seduces Tenoch which inflicts a bitter, Shakespearean angst in Julio who seeks to punish Tenoch by telling him he slept with his girlfriend. Thus begins a long and painful disintegration of their bond, which proves to be the uncomfortably confidential and subconscious bond of adolescence. Luisa attempts to rectify this situation by having sex with Julio but instead causes the violence to escalate. If we see Julio and Tenoch as the essentially innocent, customarily arrogant, premature protagonists that they are then it is Luisa who is both victim and antagonist as result of her sexual philanthropy. Tenoch and Julio experience an Oedipal desire for Luisa who is in fact almost 10 years older than they are, and the result is a near complete dependence on her. As it is, Luisa has had dependents her whole life. It is only at the point when she meets the two boys that she seeks to become a “fully realized women,” by shrinking her plane of existence to the point at which she can control every aspect of her life; shirking the responsibility she has felt toward others and freeing herself from the confines of her maternal instinct. However, there is one aspect, revealed in the final minutes of the film, that she cannot control and it is the one that fuels her progression, allowing her to move beyond the trivial ennui of modern life.

There is a scene near the end of

Y Tu Mamá También where Luisa, Tenoch and Julio are sitting around a table talking, joking and drinking. They talk mostly of sex, the sex that makes this film both intimate and controversial. Luisa imparts on the boys a very simple, adult and self-less piece of advice: the greatest pleasure is giving pleasure. Balanced and fully realized lives are contained not within the self but outside it: experiencing and exploring the canals, tunnels, and caverns of other people's lives.

Y Tu Mamá También is a coming-of-age tale as well as a departure from life anecdote. It is a double helix of a film in so many respects. Its interwoven narrative of explosive expansion and subtle contraction of vision is paralleled by the rise of Julio and Tenoch's consciousness and the fall of Luisa's desire to live amongst falsity and betrayal. The film represents the ubiquitous but not generic universality of life's music and is, in and of itself, not so much perfect as it is truly real.

No comments:

Post a Comment